German industrial design

T he quality-label “Made in Germany” depends not only on the perfection and reliability of German products but also on the quality of German industrial design.

The fact that German car brands are sought-after all over the world nowadays may also be linked to the big and long tradition of industrial design in Germany. And to a sort of cultural shock in an early phase of globalisation: at the London World Exhibition 1851 German products were branded with the (back then) negative label “Made in Germany”. The London show, which took place in the famous Crystal Palace was what initially sparked the evolution of model collections and industrial museums everywhere in Europe and thus also in Germany. Based on the patterns of the show collections the regional economy should learn what successful products should look like.

The desire for a better life

Even today, this learning by models system is testified to in museums of applied art, for example, in Berlin, Frankfurt and Cologne. The desire for better design of German products and the desire for a better life in modern times resulted in remarkable institutions such as the Deutsche Werkbund at the beginning of the 19th century as well as the Bauhaus in the 1920s with renowned and internationally active masters like Walter Gropius. After the Second World War the tradition of design education was re-established under Max Bill at the Hochschule für Gestaltung (HfG) in Ulm.Till today the impact of these educational facilities has been omnipresent in German industrial design and the historic roots are showcased in the Bauhaus Archive in Berlin and the HfG Archive in Ulm.

In Munich the Neue Sammlung in the Pinakothek offers a remarkable insight into the whole topic of German design tradition up to today. Current German industrial design is represented internationally mainly though automotive brands, and the fascination can be experienced in contemporary glass palaces: the BMW World in Munich, the Porsche Museumand the Daimler Museum in Stuttgart or the Volkswagen Autostadt in Wolfsburg. The charisma of these brands has transferred the design tomany other technical innovations from Germany, in the areas of engineering, medical technology or the creation of rail vehicles as well as other industries.

The future is awaiting

The future of German industrial design is crafted at the colleges and universities, where young talents are well educated for tomorrow’s industrial design. To secure global success of German industrial products in the future, besides other actions, the VDID (Association of German Industrial Designers) initiated the VDID NEWCOMERS’ AWARD. The results reflect the challenges shaping the future of industrial design. Some of these challenges are the themes of mobility, universal design in relation to demographic changes and the efficiency of resources for the purpose of reducing environmental burdens.

All VDID activities address current transformation processes in industrial design. Industrial designers perform the transfer of new materials and technologies between different industries and fields of application. VDID industrial designers develop new guiding principles and exercise their responsibility for the change of product culture. The current VDID Codex of industrial designers defines ten focal points of the “future” challenge and initiates analysis and debate. The selection criteria of the newcomers’ award are according to these VDID statutes.

“I Beyond”

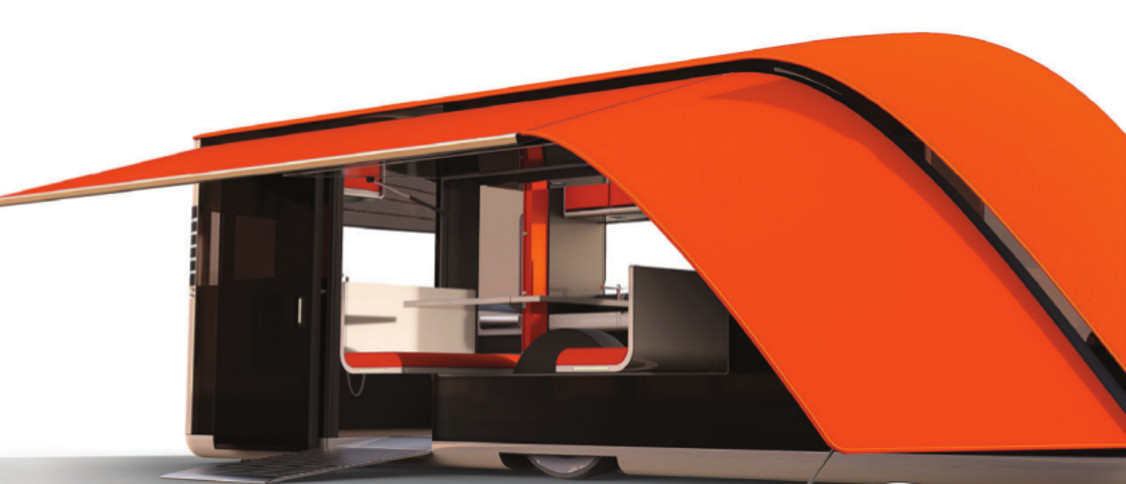

One of the VDID NEWCOMERS’ AWARD winners in 2013, Markus Kurkowski, created the interior and exterior design of a caravan. His concept called “I Beyond” encourages independence and is equally appropriate for people with and without physical disabilities. Accessibility is achieved by lowering the caravan and using a wide entrance and sliding doors. The interior furnishings can be tailored to suit individual abilities. According to the jury, this is a universal design in the best sense of the word, as it makes this object more conveniently usable by people of all generations and abilities. Another prize was given to Jan Meissner who searched for an answer to the question “How to deconstruct a skyscraper?” His idea is a solution to an urgent problem that big cities around the world are facing. His “urban mining restructuring” is a concept for the economical demolition and recycling of skyscrapers in densely built megacities that is also time-efficient. This system mechanically deconstructs a tall building “from the roof down”. It uses a frame mounted on the top of the building, exterior tunnels, shredders and sorters to transport and process the materials that are recovered — including glass, concrete, steel and waste products.

The next generation of German industrial design

An honourable mention was made of Wassilij Grod for his CONBOU – High Heel Table. A latticework construction made of bamboo sandwiched between two exterior surface materials saves renewable resources and enables a good balance between weight and construction stability. According to the jury, the designer has embraced two important aspects of sustainable product design: resource protection and lightweight construction. All designs of the 45 newcomers selected for the competition show that the next generation of German industrial design is working on the challenges of the future, through studies and in practical life and of course in multinational teams.

By Iris Laubstein / Association of German industrial designers, published in Discover Germany issue 9 – November 2013 | Photos: Association of German industrial designers

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Receive our monthly newsletter by email