Berlin city architecture guide: top 5 architectural structures

TEXT: CORNELIA BRELOWSKI

Jüdisches Museum Berlin. Photo: visitberlin, Wolgang Scholvien

Step into history and arrive in the present – Berlin’s architectural highlights will, sometimes literally, take you on a zigzag course.

You can’t get past Karl Friedrich Schinkel when writing about Berlin architecture. Nor can you skip the Bauhaus and Postwar Modernism, or contemporary additions by, say, Daniel Libeskind. When it comes to talking Berlin architecture, you need to bridge the old and the new – just as many of the landmark structures already do.

Neue Nationalgalerie. Photo: visitberlin, Jan Frontzek

Neue Nationalgalerie

Let’s start with a modern classic by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe from 1968, simply because after Weimar and Dessau, the Bauhaus masters toughened it out in Berlin for another year before being forced to close their school in 1933, and partially emigrate, in van der Rohe’s case to the US.

Recently restored, the iconic Neue Nationalgalerie mirrors the Bauhaus credo of less is more to a T, and its steel-glass structure gives the illusion of the main hall to be quasi hovering above ground. The style-defining square pavilion sits on a 105×110 metre granite terrace that compensates for the slight slope on the banks of Landwehr Canal and features a sunken sculpture garden in the back.

Neue Nationalgalerie. Photo: visitberlin, Tanja Koch

While the main hall is intended for temporary exhibitions, the basement contains rooms for the permanent collection. On the west side, the downstairs rooms are adjoined by the walled sculpture garden, which can also be seen from the higher plinth platform that extends around the hall on the first floor. Column-free, and fitted with furniture from Marcel Breuer’s armchair collection Barcelona, its ceiling features the light strips of a powerful, permanent light installation by Jenny Holzer, acquired in 2001. With its latent classicism, van der Rohe’s solution is a modern realization of the ancient podium temple, corresponding with the Berlin building tradition shaped by Karl Friedrich Schinkel and his school during the 1800s.

Altes Museum. Photo: Tatevik Vardanyan on Unsplash

Altes Museum – a gem of classicism

Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s Altes Museum is part of Museum Island, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. You could well say that half of Berlin was shaped by this master of classicism and his successors and scholars, whose buildings were considered in part revolutionary at the time.

Erected between 1823 and 1830, the two-storey classicist masterpiece consists of a flat-roofed cubic structure on a plinth, measuring 87 metres in length and 55 metres in width. From the outside, it is closed off by a vestibule with eighteen columns. The hall, bordered by two corner pilasters, opens onto the Lustgarten square. The monumental order of the Ionic columns, the wide-span vestibule, the open staircase and the rotunda – a space for contemplation and an explicit reference to the Roman Pantheon – are architectural symbols of dignity that until then had only been reserved for stately buildings.

Altes Museum within the cultural centre of Berlin Mitte. Photo: visitBerlin, Mo Wuestenhagen

During the restoration of Altes Museum after WWII which lasted until 1966, the rotunda was the only part of the interior to be reconstructed in its original form: The circular, domed room is surrounded by a gallery supported by twenty Corinthian columns. The museum was designed as an art temple for everyone under the tutelage of Friedrich Wilhelm III, and houses the Collection of Classical Antiquities.

Philharmonie Berlin with Kammermusiksaal, aerial view. Photo: visitBerlin, Artfully Media, Sven Christian Schramm

Hans Scharoun’s Philharmonie

Opposite Neue Nationalgalerie, and formerly dominating Potsdamer Platz together with the State Library, the gleaming, expressionist facade in yellow-gold underwent several stages until it became the unique and uplifting prospect that it is today. Thanks to its unusual architecture, the home of Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra stands out from the surrounding buildings of Kulturforum and is considered a prime example of organic expressionist architecture. The structure was built between 1960 and 1963 as the very first postwar building of Kulturforum ensemble on the southern edge of Tiergarten.

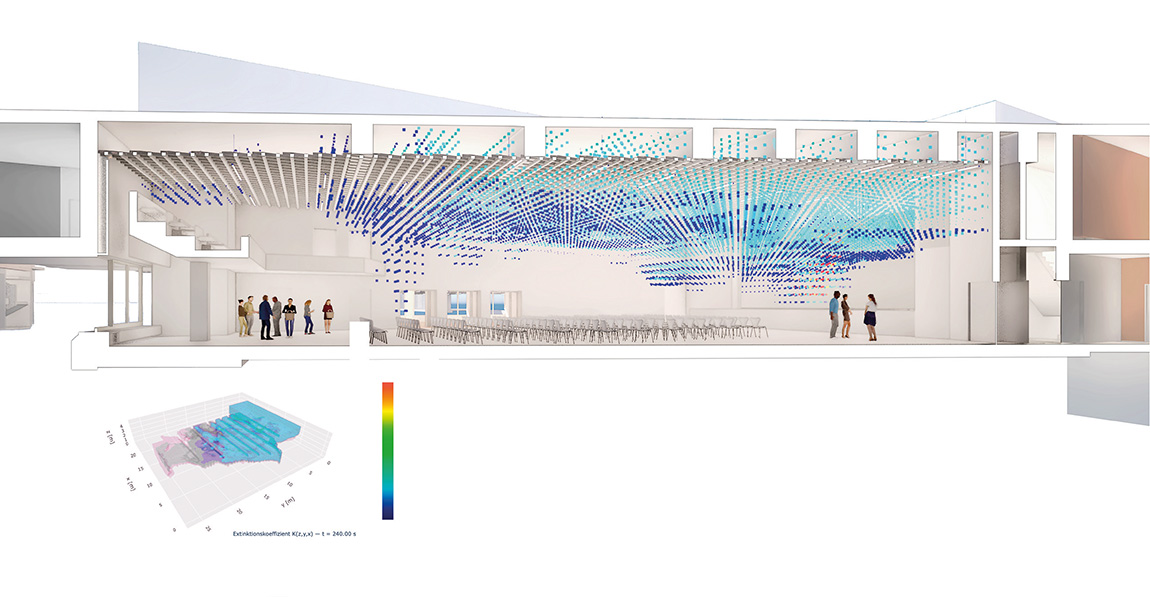

Inside, the audience is seated on all sides of the concert podium. Contrary to what many visitors assume, the convex sound elements hanging above the stage were not primarily installed for the audience, but for the musicians. With a ceiling height of 22 metres above the podium, these reflectors shorten the sound path of the early reflections, so that the instrumentalists can be heard by each other. Thus, both visually and acoustically, the orchestra literally takes centre stage in this building.

Philharmonie Berlin. Photo: visitberlin, Wolgang Scholvien

The outer shape of Philharmonie is reminiscent of the bow of a ship, a popular motif for Hans Scharoun. The façade he had planned was initially not realized because it was too expensive, and instead simulated by an ochre paint coat. It was only between 1979 and 1981 that the signature, yellow-gold aluminium panels were finally installed. Hans Scharoun himself formulated in Architectural Review in 1964; “It does not often happen in the working life of an architect that a building is carried out as it has been conceived. This has happened in the case of the Berlin Philharmonie.” The visionary building has since served as a model for many acoustics-related architectural projects, including the Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg.

The adjacent Kammermusiksaal completes the ensemble and was added in 1984-1987 using the original plans by Scharoun, realized by his pupil and office partner Edgar Wisniewski.

TV Tower at Alexanderplatz.Photo: Lukas Zischke on Unsplash

TV Tower / Fernsehturm

Towards the end of the 60s, the GDR scored points in the postwar architectural race with the space-age design of the iconic Fernsehturm at Alexanderplatz. Designed in the International Style by Hermann Henselmann and at 368 metres high, the signature tower presents the highest landmark in Germany (which may have been just what the GDR regime wanted at the time), and has provided Berliners with a compass-like sense of direction ever since its construction.

The sphere of the TV tower was intended as a reminiscence of the Soviet satellite Sputnik. For the installation of the sphere at a height of 200 metres, the supporting steel framework was prefabricated on the ground. The segments were then raised up with cranes and attached to the circular platform, which formed the completion of the concrete shaft. The sphere spins in slow motion and houses a restaurant to enjoy the 360º panorama in style.

Berlin view with TV Tower. Photo: Claudio Schwarz on Unsplash

Jüdisches Museum Berlin

Next to Norman Foster and David Chipperfield, who have both contributed considerably to the contemporary architectural landmarks of Berlin, Daniel Libeskind is to be mentioned for his highly praised extension for the Jewish Museum. It was opened in 2001 as a lively new centre for German-Jewish history and culture.

Past, present and future are the central themes of the Libeskind design. Its cause is to make people understand both the enormous contributions made by Jewish citizens to the city as well as the Holocaust and attempted erasure of Jewish culture in Berlin between 1933 and 1945. Consequently, an important part of the design is an actual void needing to be bridged. Unlike the deliberately disorienting zigzag of the complete structure – derived mathematically by plotting the home addresses of Jewish writers, artists, and composers who had lived in Berlin neighbourhoods before World War II but were killed during the Holocaust – the void cuts through it as a straight line, whose impenetrability becomes the central focus around which exhibitions are organised. In order to move from one side of the museum to the other, visitors must cross one of the 60 bridges that open onto this void.

Jüdisches Museum Berlin. Photo: visitberlin, Wolgang Scholvien

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Receive our monthly newsletter by email